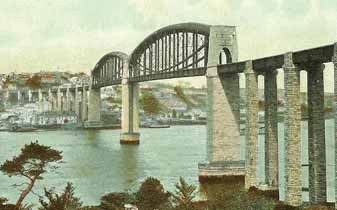

It was a late autumn day in 1973. We had just left Plymouth and turned a corner on the A38. There it was branded with letters over two metres high —

“I K BRUNEL / ENGINEER / 1859”. It was the Royal Albert Bridge.

The difficulty of its construction rates as the high point in an engineering feat that saw the Great Western Railway become the wonder of the Victorian world.

I had grown up on a diet of Isambard Kingdom Brunel. I learned of his Great Western and Great Eastern. I knew he had flown in the face of convention and insisted on a seven foot gauge for his railway.

I even knew of his attempt to launch an air-powered railway in Cornwall. Now on that fateful day in 1973 I finally got to see his remarkable Saltash bridge.

Going West

The Royal Albert is one of Brunel’s bridges that still carries trains in England’s West Country. He designed it in 1855 after Parliament rejected his plan for a train ferry across the Tamar.

It consists of two main 139m spans, some 30m above mean high spring tide, and 17 shorter approach spans. It carries trains in and out of Cornwall across the River Tamar between Plymouth and Saltash Brunel understood that passengers wanted to enjoy the romance of rail travel.

He believed trains should appear to float over the landscape in unencumbered ease. To this end he built the numerous viaducts, tunnels, embankments and even sea defences that characterise his Great Western Railway.

The Royal Albert Bridge was not only his greatest challenge but his greatest contribution to his illusion.

Spanning the divide

Brunel’s design consists of a two-span bowstring suspension bridge with a single rail track. Head room for sailing ships required a central pier. He solved this difficulty by constructing a Great Cylinder that he floated into position and sunk to act as a coffer dam.

Each of two main spans consists of a compressed wrought iron tubular arch with a parabolic profile. This is combined with a suspension chain in tension that acts to hold in the bridge abutments. The catenary curve of the chain is such that the tube’s rise equals the dip in the chain.

Between these two chords, cross bracing and suspension members beneath the chains carry the railway deck.

The spans were constructed on the Devon foreshore and floated into position. The brickwork of each pier was built up one metre at a time, and the spans raised by this amount. This was repeated until the design height was achieved.

Live fast . . .

On September 5, 1859, Brunel’s 40-cigar-a-day habit caught up with him. He collapsed on the deck of his almost completed Great Eastern and died two days later. His Saltash bridge had been opened only a few weeks earlier by the Prince Regent.

His achievements had fired the imagination of Victorian Britain. Not only did the rich and famous assemble en masse for his funeral but several thousand of his railway workers arrived to pay their respects.

In 2002 BBC viewers voted Brunel the second most important Briton of all time after Winston Churchill. A 2006 bicentenary celebration can be found at www.royalalbertbridge.co.uk.